Use rates for inpatient and certain hospital outpatient services are declining in many areas of the country, reflecting fundamental change brought by the new business model. Importantly, as evidenced by trends in Chicago and Minnesota, there also appears to be a correlation between the level and pace of a market’s shift toward value-based care and the level and pace of utilization decline.

We believe this trend is here to stay and that it has significant strategic and financial implications for health care providers. Specifically, providers that embrace the migration to value-based care will need to work aggressively to eliminate unnecessary and/or ineffective activities in order to thrive under risk contracts. This requires a fundamental change in mindset, culture, and attitude about volume and activity. It also requires providers to rethink the organization and structure of their delivery networks to avoid supporting unnecessary capacity, and to drive patients into the lowest-possible cost setting in which quality care can be delivered.

The goal will be to manage a population’s health across the care continuum, keeping patients healthy through preventive and primary care services, and out of acute care facilities whenever possible. The right place to provide the right care at the right time with the right quality, cost, and access increasingly will be a setting other than a hospital. By eliminating waste and redirecting patients to ambulatory centers, physician offices, clinics, and online and/or telephonic interactions, less work will be done in the hospital. To reduce well-documented overutilization, tests and services deemed inappropriate or unnecessary based on medical evidence will be eliminated in all settings. (See Note 1) Acute care will be one, and only one, component of the population-centric health management services continuum.

Those providers that choose not to participate in the movement toward value-based care will suffer the consequences of an economic livelihood tied to a business model based on a level of “activity” that will deteriorate significantly.

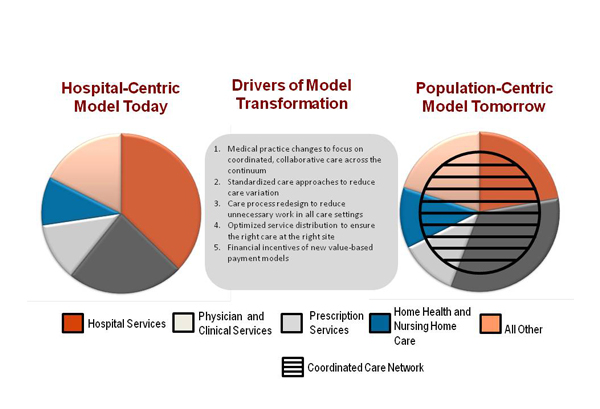

As health care transforms from a hospital-centric to a population-centric model (Figure 1, click to enlarge), the speed of utilization decline will vary by market or region, but growth-rate declines — leading possibly to real declines in volume — could occur across much, if not most, of the nation. The needs of aging baby boomers, and those newly insured through provisions of the Affordable Care Act, may slow utilization declines in the short term, but are not likely to diminish lower inpatient use rates long term.

Federal and state fiscal challenges, and the growing proportion of U.S. gross domestic product consumed by health care, ensure that the downward pressure on use rates is here to stay. Factors lowering utilization will be cumulative and interdependent. In addition to macroeconomic forces, drivers bending the utilization/cost curve include:

- changes in medical practice that focus on coordinated, collaborative care across the continuum;

- increased use of standardized care approaches to reduce care variation;

- care process redesign to reduce every bit of unnecessary work in all care settings;

- optimized service distribution to ensure the right care at the right site; and

financial incentives of new value-based payment models that reward elimination of waste and redirection of patients

to lower-cost settings. - All health care executives and trustees must be paying full attention to these developments, even if they are in geographic areas not yet affected. A close look at the utilization data, the types of initiatives accelerating the downward trend, and the key implications for hospital and health system leadership follow.

Figure 1. Drivers and Effects of Value-Based Care

Source: Kaufman, Hall & Associates, Inc.

Already Down: A Look At The Recent Past

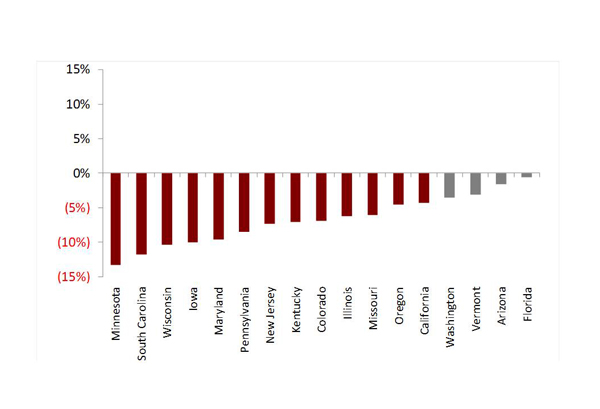

Declining utilization is not a new trend, but one that has been developing for the past five to 10 years. A multistate study conducted by Kaufman Hall, encompassing nearly half of the nation’s population, indicated that inpatient use rates per 1,000 declined significantly between 2006 and 2011. (See Note 2) Seventy-one percent of sample states had drops greater than 5 percent, ranging from a decline of 0.6 percent in Florida to 13.3 percent in Minnesota (Figure 2, click to enlarge). Declining inpatient use rates occurred for all age groups. (See Note 3) While many experts cite the recession as the key cause of this trend, the greater than 10 percent use-rate drops for those age 65 to 84 — whose health care costs are largely covered by Medicare — signal that other factors, such as the drivers cited earlier, also are at work.

Figure 2. 2006-2011 Change in Inpatient Use Rates per 1,000

Source: Analysis by Kaufman, Hall & Associates, Inc.

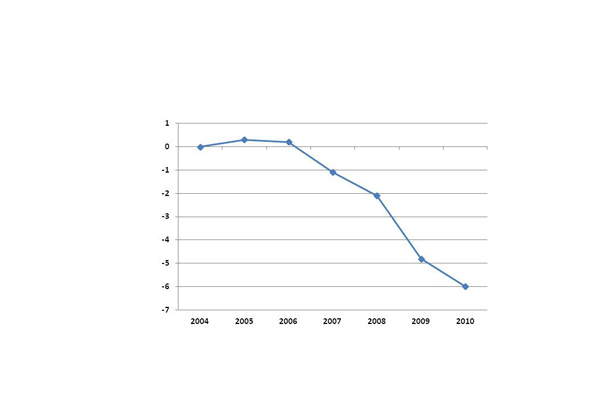

Government data mirror this downward trend. The cumulative inpatient discharges per fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiary declined 6.0 percent from 2004 to 2010. (Figure 3, click to enlarge) These data from MedPAC’s analysis of claims from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) likely reflect success of federal efforts to shift care of Medicare beneficiaries to outpatient settings, as appropriate. A specific component of the decline is likely related to Medicare patients who formerly were admitted with acute heart health issues who now are being cared for in an observation or clinical decision unit.

Figure 3. Cumulative Change in Medicare Inpatient Discharges per FFS Beneficiary, 2004-2010

Source: MedPAC: A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program, June 2012.

Although outpatient services are still increasing, economists from CMS’s Office of the Actuary noted a slowing of growth in outpatient visits and surgeries. Data released in October 2012 by the U.S. Census Bureau show a decline in annual medical services utilization among people ages 18 to 64 from 4.8 provider visits in 2001 to 3.9 in 2010. The volume of growth that is occurring is taking place in non-hospital settings, according to the McKinsey Center for U.S. Health System Reform.

Comparative Use-Rate Declines

Many markets and organizations have experienced even more significant declines since the recession officially ended in June 2009. A close look at specific examples reveals some of the drivers likely to permanently bend the use curve.

For example, in Minnesota, which had drops of more than 13 percent, the state’s health systems pioneered the use of new care and payment models, including medical homes, value-based purchasing by employers, shared-savings and quality-improvement managed care contracts, community-based management of patients with chronic diseases, e-health initiatives, and accountable care organizations (ACOs). Minnesota now ranks No. 4 in the nation for access, prevention and treatment, avoidance of hospital use, and lower costs of care in The Commonwealth Fund’s scorecard for “high health system performance.”

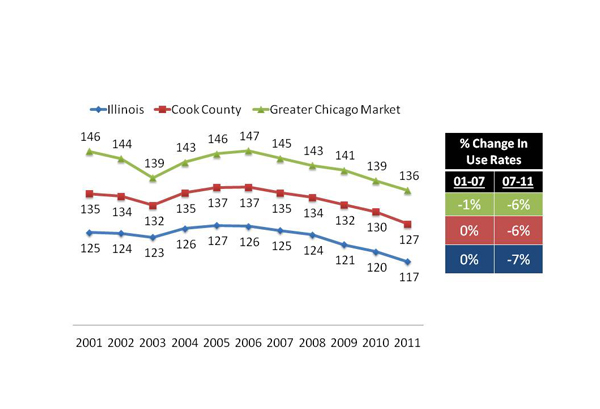

In the greater Chicago area, Advocate Health Care and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois (BCBSIL) developed and are operating one of the nation’s most-watched new value-based care models. Advocate’s success in reworking the system to align incentives for value-based care under a population health management contract with BCBSIL appears to be helping to push the entire Chicago metro market toward lower utilization. Inpatient use rates per 1,000 in Chicago, Cook County, and Illinois have decreased by 6 percent to 7 percent between 2007 and 2011. (Figure 4, click to enlarge) Advocate’s own most recent numbers, comparing data from second quarter 2012 to second quarter 2011, show per-1,000 decreases of 8.7 percent for inpatient days, 6 percent for admissions, and 4.1 percent for prescriptions. (Data for second quarter 2012 provided through personal communication with Lee Sacks, M.D., October 2012.)

Figure 4. Inpatient Use Rate Trends in Chicago Area, Cook County, and Illinois

Sources: Analysis by Kaufman, Hall & Associates, Inc. using data from Claritas 2000/2012 estimates, and Illinois Department of Public Health inpatient hospital discharge data from January 2001 through December 2011.

New care models also are having an impact at Sharp HealthCare in San Diego, where an innovative program called “Transitions” is providing Medicare managed care patients with palliative care options. The program uses a population health management approach to identify people at the beginning of an illness who could require palliative services and then provides them four services: in-home skilled care; evidence-based prognostication to help doctors be more open about the likely course of a patient’s illness; care for the caregivers; and goals-of-care discussions. With heart failure patients, who typically experience falls, medication issues, and caregiver problems that lead to hospitalizations, the results are already dramatic — a 94 percent reduction in emergency department visits. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, and end-stage cancer will be the next diagnoses to be included in the Transitions program.

To reduce unnecessary imaging, which is a well-documented problem, Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle now requires referring physicians ordering MRIs for back pain or migraines to designate one of a list of evidence-based indications. When such decision rules were embedded in the scheduling process, MRI volumes declined 31 percent for back pain and 41 percent for headaches.

Doctor-centric models are driving real results. The care model at HealthCare Partners (HCP) (purchased by DaVita in May 2012), which operates physician groups and networks mostly through capitated arrangements, puts physicians in the leadership role at the center of patient-focused integrated care. HCP is clinically and financially accountable for meeting all health care needs of an enrolled patient population and managing the related risk. Its disease management programs offer more frequent physician visits, a care team approach, and immediate intervention when needed. By investing in providing care in the most appropriate setting, inpatient acute-care bed days per 1,000 patients in HCP’s senior program in California were approximately half those of patients in the state’s Medicare fee-for-service program (864 versus 1,706 days). With COPD patients, the program lowered total bed days by 39 percent, ED visits by 23 percent, admissions by 30 percent, and overall per member per month cost of care by 34 percent.

Payer-led efforts with new payment models also are producing strong results in local markets. CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield, which covers individuals in Maryland, Washington D.C., and Virginia, organized independent physicians into a patient-centered medical program, providing physicians with payment incentives to hit quality and efficiency targets. The results in its first year of operation were $40 million worth of cost savings from unnecessary hospital visits, particularly by patients with diabetes and other chronic illnesses.

Staying Down: Future Utilization Rates

Many use-reduction opportunities are on the radar screens of various industry stakeholders. Hospitals, health systems, and commercial and governmental payers are focusing efforts in the inpatient arena on “preventable” hospitalizations for acute and chronic conditions, preventable readmissions, emergency department use, and unnecessary physician visits. The focus is on ensuring patients receive home-based disease management programs and outpatient care, instead of accessing hospital care.

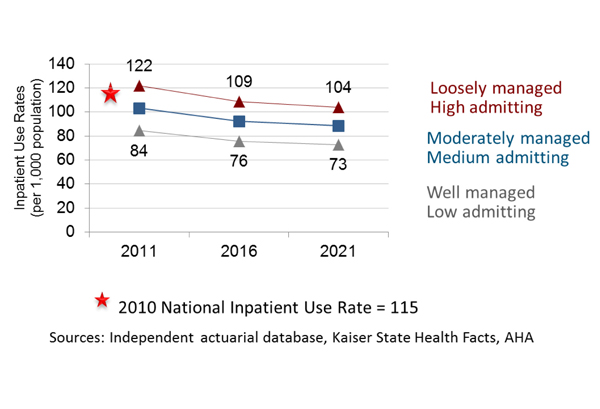

As a result, inpatient admissions per 1,000 are projected to decline through 2021 in all markets, whether care is “loosely,” “moderately,” or “well” managed in these areas. Figure 5 shows the 10-year trend line as estimated in a private study conducted in 2011 using 2010 actuarial claims data for a significant portion of the nation’s commercial insurers. “Moderate” levels of management are likely to be more representative of aggregate best practice for overall levels of medical service utilization, with inpatient admissions per 1,000 projected to drop from 103 in 2011 to 88 in 2021.

Figure 5. Projections for Inpatient Use Rates for Total Population (2011-2021)

As specific patient services migrate from the hospital to lower-acuity settings, there may be a short period of uptick in physician office or clinic visits for patients with chronic conditions. In the outpatient arena, per-1,000 use rates for office, home, urgent-care, and physical-exam visits are expected to increase in moderately managed environments from 3,554 in 2011 to 3,574 in 2016, and then decline to 3,208 in 2021. Drops are projected in outpatient MRI and CT testing and ambulatory surgery.

Implications For Hospitals And Health Systems

The end of the hospital-centric model will change how hospitals participate in their local care delivery systems, presenting hospital leadership with significant new requirements to maintain an organization’s essentiality in its community.

Culture. The most fundamental requirement for hospital leaders will be a mindset or cultural shift that is oriented toward delivering value, and not necessarily acute-care diagnostic and treatment activity. The culture shift needs to be framed within the context of delivering quality care and doing the right thing for the patient. Clinical activity that is not indicated by the patient’s condition must be moderated or eliminated. Being accommodating to requests for the next test or service may not be appropriate. Physicians, patients, and family must participate in this shift; education and incentives will be needed.

Physicians and Care Delivery. A strong physician platform will be mandatory to hospital success going forward. To drive the real change that lowers utilization, physicians who are employed, affiliated, and independent must be organized and incentivized for value-based care. Physicians should lead the care redesign effort, eliminating inefficient, ineffective, or unnecessary processes in the hospital setting. When care is indicated, physicians must direct the patient to the lowest-cost setting possible. In consultation with experts and physician leaders, hospital management teams can identify and implement the specific physician-hospital integration models that will produce the needed cultural, financial, and clinical changes in their communities.

Communication and HIT. The provision of high-quality care in lower-acuity settings — whether in homes, clinics, physician offices, post-acute facilities, or other sites — will present communication and coordination challenges of a magnitude not encountered in the hospital-centric model. To support effective communication and efficient care delivery beyond the hospital walls, hospitals will need to continue taking the lead in developing and maintaining health information technology (HIT) infrastructure and capabilities. The ability of other organizations in the care continuum to do so is limited. Hospital-financed HIT data and analytics will be key to determining what appropriate care is, and is not, across a hospital’s delivery system. Analytics will support care delivery redesign by driving care-efficiency improvements.

Facilities. Capacity planning and major building projects that are in the early stages should be rethought and reevaluated by hospital leadership teams. Organizations can no longer sustain the costs associated with overbuilding or duplicating expensive services in many locations. Conversely, investments may be necessary and helpful in lower-intensity cost settings, such as immediate care centers and clinics, physician offices, and ambulatory sites. Efficient use of all current resources, and rationalization of services and facilities throughout a system and region, will be critical.

Contracting. Providers may need to take the lead in pushing insurers toward value-based care, as insurer receptivity to value-based concepts varies widely across markets. Again, we reference Advocate Health Care, whose leaders worked hard to obtain the support of Illinois insurance plans to experiment with shared savings and quality-improvement incentives. The faster providers can develop competencies and build a value-based patient population, the better.

Making the Transformation. Hospitals will operate in both a fee-for-service and value-based payment system during at least the next three to five years. However, it is essential that health system boards and executive leaders begin work now to prepare their organizations for a value-based world with a much different utilization profile. Provider revenues will be under severe pressure as volumes decline through marketplace and providers’ own initiatives. A revenue solution will not be available. Proactive organizations are taking steps to fundamentally restructure their approach to service delivery by redesigning care (particularly for patients with chronic conditions), eliminating unwarranted clinical practice variation, reorganizing their service delivery system, and driving down costs.

Spurred by declining utilization, health care’s business model is changing. To achieve success in a value-based system, hospitals and health systems will be required to reassess existing leadership and business models, and transform the care delivery system in their communities.

Note 1.Excess health care utilization and waste is well diagnosed and publicized from credible sources. Among them are:

- The Institute of Medicine estimates that “unnecessary services” yield excess costs of $210 billion.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data show that the median number of MRIs per 1,000 in developed countries is 43, but is 91.2 in the U.S.; similarly, median CT scans per 1,000 in developed countries is 122.8, but is 227.9 in the U.S.

- Consumer Reports and physician specialty groups have identified and publicized tests and procedures that are overused or unnecessary.

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimated as part of its Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project that one out of every 10 hospital stays in a recent year was potentially preventable.

Note 2.Sources include U.S. Census Bureau 2006-2010 Population Estimates; HCUP State Inpatient Databases; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council; Illinois Department of Health and Human Services; and AHCA data set for Florida.

Note 3.The weighted average changes in inpatient use rates per 1,000 were 6.9 percent for ages 0-17; 7.0 percent for ages 18-44; 4.6 percent for ages 45-64; 11.2 percent for ages 65-84; and 7.0 percent for ages 85 and over. Weighting was based on state population as a percentage of total sample size population; discharges exclude normal newborns.