The Yale Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT) is a proactive, multi-disciplinary psychiatric consultation service for all internal medicine inpatients at Yale-New Haven Hospital. The goal of the team, which includes nurses, social workers, and psychiatrists, is to shift from a “reactive” to a “proactive” paradigm of psychiatric consultations on hospital inpatient medical floors.

The team screens for, identifies, and removes/mitigates behavioral barriers to the effective receipt of health care among hospitalized medical patients, especially among those with co-occurring mental illness and/or substance abuse. To facilitate delivery of timely, effective inpatient medical care, the BIT collaborates closely with the medical team through formal and informal advice, co-management of behavioral issues, education of medical, nursing, and social work staff, and direct care of complex behaviorally disordered patients. The team also assists the primary medical treatment team as needed with transitions to the next level of care involving behavioral health services.

Standard “Reactive” Psychiatric Consultation Challenges

We implemented this change in our psychiatric consultation service paradigm because the standard “reactive” psychiatric consultation paradigm was not as effective as all the stakeholders wanted and needed. The Behavioral Intervention Team was created to address the following challenges to the hospital’s provision of care to medical patients with co-occurring psychiatric (also known as “mental” or “behavioral” health) or substance abuse issues:

- Psychiatric problems have become a significant barrier to the delivery of efficient, high quality medical care, largely due to increased numbers of co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses, stigma, and lack of training and education among medical staff for handling psychiatric problems.

- Psychiatric consultation requests were often too late to alter a full-blown crisis or were requested for issues that were trivial or inappropriate.

- Psychiatric consultations were usually provided to the physicians in writing and had an air of formality that did not support the give and take of supportive education among peers.

- Mental health clinicians were not reaching the people who spent the most time with the patients, namely the nurses.

- Post-hospitalization transitions in care for mental health services were frequently poorly managed by the primary medical team without input from the psychiatric consultation team.

- Health care workers without training in mental health care were increasingly experiencing distress and demoralization when they had to take care of psychiatric patients, thereby reducing their job satisfaction and work effectiveness.

Overall, the traditional, physician-focused psychiatric consultation service model is reactive and too slow to capture the fast-moving, complex elements of mental illness, creating havoc in a general medical ward. We needed a change.

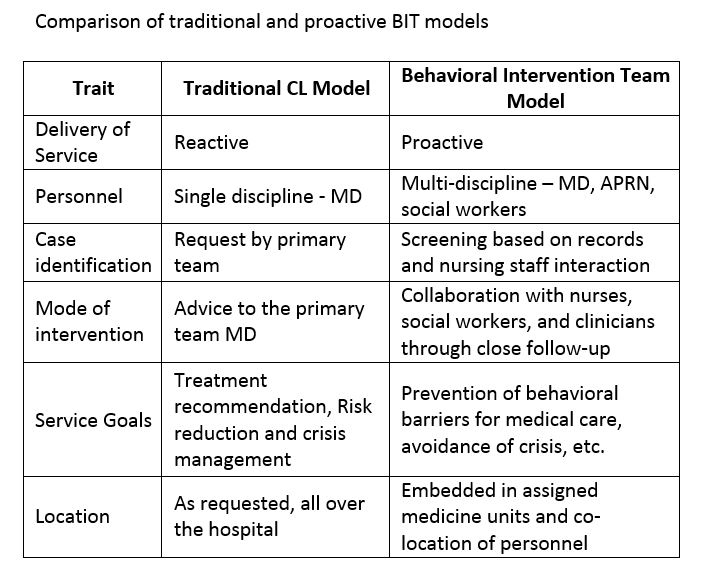

Table 1 summarizes and compares some of the qualities of a proactive and reactive consultation service in psychiatry.

Table 1

The Experiment’s Beginning

We began by testing the hypothesis that patients could be screened rapidly and effectively at admission for psychiatric service needs and early “proactive” consultation. We asked whether such a system actually had an advantage over a “reactive” consultation.

For six weeks, we embedded a psychiatrist into the admissions process of a medical unit with a high rate of psychiatric co-morbidity. We focused our efforts on patients with co-morbid mental health and substance abuse disorders whose conditions, we believed, were hindering (or threatening to hinder) the provision of inpatient medical care. A psychiatrist went to the test unit every morning, screened all patients proactively, and usually provided consultation on the identified patients on the first or second day of their medical admission.

This six-week experiment produced surprising results. The length of stay for all admitted patients in the test unit for six months prior to our experiment was roughly four days, with a 9 percent consultation rate. During the proactive phase of the experiment, the consultation rate increased to 22 percent, and the length of stay decreased by almost 25 percent.

When the proactive phase stopped, and the test unit returned to the prior reactive approach, the consultation rate dropped to 13 percent and the length of stay increased to almost four days, as it was before the experiment. This single case study provided evidence of a potential cause and effect relationship between a proactive consultation model and reduced length of stay in medical services at Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Based on the successful results of this experiment, and with the support of the hospital administration, we created the Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT), a multi-disciplinary, proactive consultation, education, and management approach to address the behavioral service needs of medical inpatients. The BIT took on consultations and, when appropriate, co-management of complex psychiatric patients, educated the staff, and helped manage extra nursing care when additional supervision was necessary for specific patients. The BIT also managed the relationship with the insurance company when a required psychiatric bed was not immediately available.

To implement the BIT program, we assigned a half-time consulting psychiatrist, a full-time mental health clinical nurse specialist, and a full-time psychiatric social worker whom together covered roughly 75 inpatients on three medical units. In a subsequent 11-month study with a “before and after” design, the target medical units had a consultation rate of about 15 percent and reduced the length of stay by 0.65 days among medical patients with a psychiatric intervention. In addition, there was a 0.3 day length of stay reduction for all admitted patients in the medical units compared to the two years prior to implementation of the BIT model on the same units.

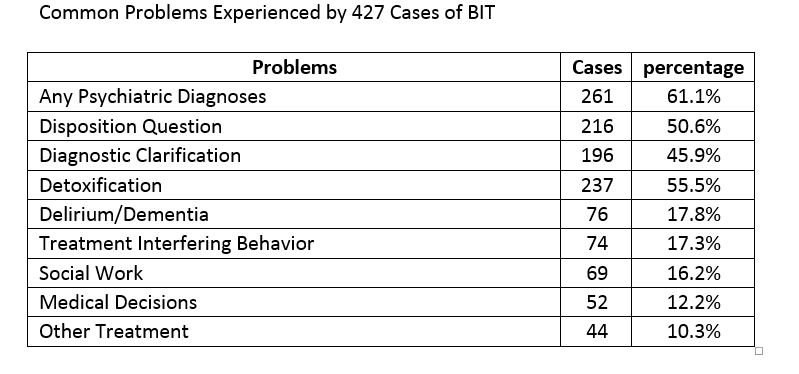

We believe this overall reduction in length of stay may be a function of the “curbside” effect of informal, non-billable consultations by the BIT, thereby improving the work efficiency of the medical personnel generally (i.e., nurses and doctors were consequently less burdened by unfamiliar aspects of care of psychiatric co-morbidities). The results of this work, authored by Sledge, Gueorguieva, Desan, Bozzo, Dorset, and Lee, are in press and are due to be published during 2015 in the journal, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. The ranges of conditions that were formally consulted upon are noted in Table 2.

Table 2

BIT’s Today

In the current and third iteration of the program, the BIT is on all eight general medical units at our York Street Campus, covering roughly 192 patients. There are two teams comprising between them 1.75 full-time equivalent (FTE) psychiatrists, two advanced-practice registered nurses (APRNs), and three social workers with a clinical nurse specialist who administers the teams.

In addition, there is robust weekend coverage of a social worker, a resident (24 hour coverage), and an attending psychiatrist who provides multidisciplinary, partially pro-active psychiatric consultations for the entire hospital (approximately 960 beds). The current BIT also helps manage the costly utilization of constant companions assigned to patients with acute behavioral issues (e.g., runaway patients and suicide precautions).

Today, the BIT screens daily for possible and active behavioral problems (e.g., substance abuse, mood and psychotic disorders, agitation, etc.) among all medical patients upon admission to the general medical services of the Yale-New Haven Hospital York Street Campus. Screening is based on review of admission notes from the electronic medical records and on patient’s interaction with the admitting nursing staff. This activity is carried out early in the morning by the APRNs or the social workers.

Upon identification of one or more active behavioral issues that could interfere with the delivery of effective, efficient inpatient medical service, a BIT clinician (APRN or physician) provides a formal psychiatric assessment and ongoing follow-up during the hospitalization. The BIT is designed to identify and treat/manage active behavioral problems at the earliest possible time during the hospitalization. As a result, decisions about which patients will receive formal assessment are made in a huddle at mid-morning. By focusing on early recognition, the BIT seeks to mitigate the effects of patients’ mental or substance abuse disorders on their physical recovery.

Concurrent with the clinical evaluation, the consulting BIT members educate their corresponding discipline personnel (physician to physician, nurse to nurse, and social worker to social worker) of the medical team on the salient clinical aspects of acute and chronic medical management of the particular patient. In addition, by embedding a mental health care provider in the inpatient medical setting, there is extensive “curbside” advice and informal collaboration among the BIT team and the primary medical team members for all patients with behavioral health problems, including those who would not otherwise receive care without formal psychiatric consultation. We consider this “curbsiding” a form of proactive, just-in-time education.

The BIT blends well with other hospital-based programs that attempt to manage length of stay and re-admission rates. Also, the presence of an effective and partially proactive BIT service on the weekend has had a substantial impact on the patient flow for the rest of the week. There are no longer long patient lists on Mondays and Fridays, and more patients are able to be discharged on the weekend and not forced to wait for “psychiatric clearance.”

Outcomes

We rigorously evaluate and measure outcomes. While we focus on reducing length of stay, we do not view such reduction as the main goal but rather as a proxy for the efficiency and effectiveness of the model. Reduced length of stay also pays for the intervention. Our ultimate goal is to improve the care of psychiatrically co-morbid medical patients in the hospital. The presence of an active mental illness diagnosis adds on average (depending on the setting) between 0.8 and 1.2 days to the length of stay in our settings. We seek to reduce this added burden to zero.

A commonly noted challenge of the BIT model is that it requires an extensive outlay for personnel costs that exceeds direct revenue generated by the heightened psychiatric clinical service. However, through cost-saving and revenue enhancement opportunities, we have demonstrated a return on investment ranging from break-even to four-to-one for every dollar spent.

The success of the BIT depends on a prospective payment system that rewards efficiency and reduction of expensive inpatient services. The power and effectiveness of the BIT model lies in mitigating and reducing the disruptive influence of mental illness on the daily clinical milieu of the medical staff and patients as well as reduction of prolonged and unnecessary hospitalization.

Our work has spawned other proactive, collaborative behavior-focused programs at Yale-New Haven Hospital, including a Sickle Cell Disease program. Recognizing the impact of behavioral health problems on the prolonged length of stay for Sickle Cell patients, the hospital developed an interdisciplinary “medical home” approach involving psychiatry, hematology, social work, and nursing.

Looking Ahead

In the future we aim to improve the effectiveness of the BIT program by developing standardized screening methods that can be more easily disseminated systematically and taught to others. We also want to explore the early introduction of active, specific mental illness treatments as needed, which can be a means of integrating general health and mental health services more effectively.

For example, a depressed patient might be able to start a course of medications while still in the hospital. The BIT of the future should also address the post-hospital outpatient phase. We believe this integration would improve the care of our patients by bridging the gap between the hospital and downstream treatment programs.

We intend to expand BIT throughout the Yale New Haven Hospital System and to implement new versions of BIT for specialized programs such as cardiovascular services and our cancer center. Patients with cardiovascular disease typically have short hospitalizations, so we will focus on proactive delivery of mental health services (particularly for depression and anxiety) and integration of their cardiac and mental health care in a rehabilitation program. Such a focus on transitions to cardiac rehabilitation will reduce subsequent re-admissions.

With cancer patients, we will focus on the acute distress of initial diagnosis along with neuropsychological changes and disruption of cancer treatments in the aftercare due to behavioral issues. We will integrate oncology and mental health services and, when needed, palliative care services. With cardiac illnesses, we will probably focus primarily on problems of depression, distress, and delirium, as these seem to be the most common disruptive diagnoses.

We believe that this method of providing proactive inpatient psychiatric consultation to hospitalized medical and surgical patients will prove to be a sustainable and perhaps even necessary paradigm shift in order to fully meet the triple aims of health care reform.